While we all like to think that we are capable of making rational decisions, it appears that when it comes to investing, a switch inside even the most sensible person seems to flick, and rationality disappears in a cloud of emotion.

Being an investor is not easy. We have to contend not only with the erratic and unpredictable nature of markets but also the sometimes erratic and irrational way in which we will be tempted to think and behave. All investors should try their best to make rational decisions and to make their head rule their heart. Yet for many, while understanding that being rational makes sense, putting it into practice can be exceedingly difficult. Benjamin Graham, one of the great investment minds of the twentieth century, famously stated:

‘The investor’s chief problem – and even his worst enemy – is likely to be himself.’

Irrational investing manifests itself in many different ways: chopping and changing one’s investment plan influenced by what has just happened to the markets; trading shares in an online brokerage account; trying to pick market turning points, i.e. when to be in or out of different markets; being tempted into buying flavour of the month investment ideas or products; or chasing fund performance. The list of irrational decision-making opportunities is long and undistinguished. John Bogle summed this up perfectly in an address to the Investment Analysts Society of Chicago (2003):

‘If I have learned anything in my 52 years in this marvellous field, it is that, for a given individual or institution, the emotions of investing have destroyed far more potential investment returns than the economics of investing have ever dreamed of destroying.’

The ’emotional cost’ of investing can, at times, be extremely large. By emotional costs, we mean the impact on returns that are caused by our own actions or inactions (i.e., our behaviour), rather than the markets. The temptation to try to get in (or out) at the right time is huge. Imagine if you could have avoided the 50% market fall during the global financial crisis of 07/08, or the blink-and-you’ve-missed-it COVID crash in early 2020 and bought in again at the bottom. By and large, investors have a woeful track record of timing when best to jump in and out of markets. It is worth remembering that you have to get two decisions right when market timing. The first is when to get out. The second is when to get back in again. The problem is that markets work pretty efficiently at reflecting new information into prices (of e.g. company shares and bonds) quickly, and thus every decision you make is a bet against the aggregate view of all investors trading in the markets. Markets move on the release of new information which is, by its very nature, random.

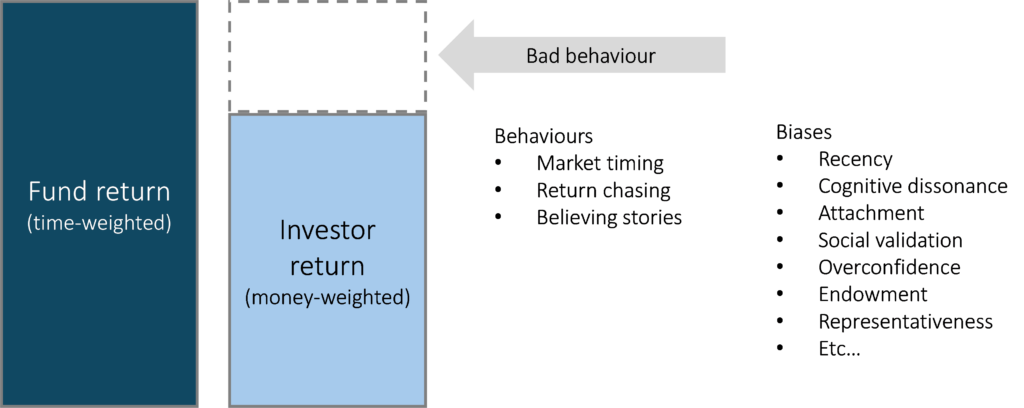

The returns that a fund deliver are known as time-weighted returns. The return an investor in a fund actually receives is known as the money-weighted return and will be impacted by the magnitude and timing of cash flows into or out of the fund that they make. A well-known piece of research from Morningstar’s ‘Mind The Gap (2023)’ report estimates this ‘behaviour gap’ to be around -1.7% per year on a large sample of US funds.

Figure 1: The emotional costs of investing in theory

Source: Albion Strategic Consulting (from ‘Smarter Investing, 2004. FT Publishing © All rights reserved)

Let us look at an example of the ‘behaviour gap’ in action. The chart below shows the fund flows of the largest index fund in the world – the Vanguard Total Stock Index Fund – plotted against the rolling quarterly returns of the fund (in GBP terms). Following the COVID drawdown, negative fund flows persisted in the following months yet the market bounced back and was up 22% by the end Jun-20. This is the behaviour gap in action.

Figure 2: The emotional costs of investing in practice (3/2019-12/2020)

Source: Morningstar Direct © All rights reserved. Ticker: VTSMX

The solution? Own a sensibly diversified portfolio with sufficient higher-quality, shorter-dated bonds to provide protection from portfolio falls, allowing you to stay invested throughout these inevitable episodes of market turmoil that arise from time to time. As John Bogle, the founder of Vanguard used to say:

‘This too shall pass!’

Investment Risk Warning

Please remember the value of your investments and any income from them can go down as well as up and you may get back less than the amount you originally invested. All investments carry an element of risk which may differ significantly. If you are unsure as to the suitability of any particular investment or product, you should seek professional financial advice.

Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made that the stated results will be replicated.

Use of Morningstar Direct© data

© Morningstar 2024. All rights reserved. The information contained herein: (1) is proprietary to Morningstar and/or its content providers; (2) may not be copied, adapted or distributed; and (3) is not warranted to be accurate, complete or timely. Neither Morningstar nor its content providers are responsible for any damages or losses arising from any use of this information, except where such damages or losses cannot be limited or excluded by law in your jurisdiction. Past financial performance is no guarantee of future results.