Time in the market vs timing the market

One of the greatest temptations in investing is to try to time when to be in or out of markets. It is logical to want to be fully invested in the equity markets when they are going up and to be in cash when they are going down.

Yet logic transforms into emotion at times when markets feel a little bit frothy on the upside, such as the late 1990s or even 2020-21, or full of gloom and despair on the downside, such as the depths of the technology crash in 2003, global financial crisis between 2008 to 2009 or more recently as quarter 1 in 2020, the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The first decision an investor faces is when to get out of the market, the next decision is when to invest in the market again, and vice versa. It would be great news if there a was a clear, proven signal that allowed us to make these calls, but as John C. Bogle, the founder of Vanguard once said:

‘Sure, it would be great to get out of the market at the high and back in at the low. But in 55 years in the business, I not only have never met anybody that knew how to do it, I’ve never met anybody who met anybody that knew how to do it.’

Hopefully this does not come as a surprise to you. Markets do a pretty good job of incorporating new information into prices quickly. This information would include any signal that now is the time to get out of (or into) equity markets. Any new information is, by definition, a random event.

Based on this, we have run a quick market timing experiment. We have taken the returns of the developed global equity markets and cash from 2000 to 2001 and adopted the following three simple investment strategies:

- Buy Hold Rebalance

This simply takes 50% of the equity return and the cash return every year and rebalances the portfolio.

- Market timing strategy 1 – ‘On a Roll’

If the previous year’s equity return is higher than the average return of all years , allocate 100% equities, if not allocate 100% to cash.

- Market timing strategy 2 – ‘Contrarian’

If the previous year’s equity return is lower than the average return of all years, allocate 100% equities, if not allocate 100% to cash.

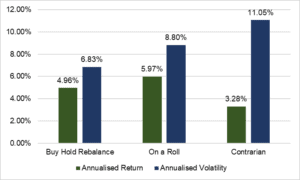

The following strategies produced the following outcome:

Source: FE Analytics

We accept that this data is limited, an investor would not know what the average return would be for all the years, we have simply used this approach for illustrative purposes.

From this data though, we can see that the “On a Roll” strategy would have yielded a marginally higher return (1.01% additional annualised return) than the “Buy Hold Rebalance” strategy. It is not all good news though, as this return was delivered with higher risk, as measured by portfolio volatility, 1.97% increase, when compared to the. “Buy Hold Rebalance” strategy.

The second take away is that the second market timing strategy, “Contrarian”, has delivered significantly reduced returns with substantially higher risk.

In addition to volatility, market timing strategies, in real life, may come with other material risks and costs, such as time out of the market when buying and selling and thereby missing the few days that make a major contribution to positive market returns, incurring the transaction costs of buying and selling and potential tax consequences.

According to Dimensional Fund Advisers, from 1990 to the end of 2020, an investment of $1,000 into US equities (S&P 500 Index) would have grown to around $20,451. Yet missing the best 15 days throughout this whole period delivered around $7,080. Missing the next 10 best days reduced the growth to $4,376. Over the same period, cash returned $2,2451 .

Other periods, or other strategies, might well result in different outcomes, but that, to some extent, is the point. There are no simple ways to time markets. Even if an investor does not believe that they can time markets, the temptation is to believe that some professional fund managers have complex models (or intuitive skill) that allow them to do so. Unfortunately, research suggests that these skilled managers are few and far between. One such global study of professional multi-asset fund managers2, who have the scope within their mandates to time markets, came to the following conclusion:

‘Overall…we find evidence of only a tiny minority of funds with asset class timing ability.’

Not much of an acknowledgment for market timing! The challenge of how to sort the wheat from the chaff should not be underestimated. The sage advice of Warren Buffett3, acknowledged as one of the world’s great investors, is also worth reflecting on.

‘Investors, of course, can, by their own behavior make stock ownership highly risky. And many do. Active trading, attempts to “time” market movements, inadequate diversification, the payment of high and unnecessary fees to managers…can destroy the decent returns that a life-long owner of equities would otherwise enjoy.’

Based on the above, our view is that time in the market is preferable to timing the market for longer-term investors seeking a successful investment experience. It may be difficult when emotions are telling you to get out of the markets but preserve and stick with it.

Investment Risk Warnings

This article is distributed for educational purposes and should not be considered investment advice or an offer of any security for sale. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but is not guaranteed.

Please remember the value of your investments and any income from them can go down as well as up and you may get back less than the amount you originally invested. All investments carry an element of risk which may differ significantly.

If you are unsure as to the suitability of any particular investment or product, you should seek professional financial advice. Tax rules may change in the future and taxation will depend on your personal circumstances. Charges may be subject to change in the future.